Sound of the Outmarsh is an ongoing project which considers the role that marshland plays in protecting and sustaining human and non-human environments and ecologies. Based on first-hand research, experimentation, and imagined futures these works focus on storylines and solutions for survival. Using ephemeral materials from Lincolnshire’s hauntingly beautiful wetlands, each embodies something of the self-organising properties of the dynamic marshland itself.

All habitats are active but marshland particularly so. Its capacity to move across the earth's surface in response to global processes and environmental disturbances (such as sea level rise) can be observed in comprehensible timescales. Marshland’s self-rising mechanism is central to its ability to renew, rebuild and survive.

The local benefits of marshland are many. Examples include vital storm and flood protection, essential feeding grounds for migrating birds and fish nurseries as well as important breeding sites for grey seals. Less apparent, however, is the significant protection it provides globally. Like other wetland habitats, marsh absorbs and stores large quantities of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and ‘pound for pound,’ this can be 10 times greater than that of mature tropical forests. This is their superpower. Not everyone lives close to a marsh, but everyone benefits from its many layers of projection.

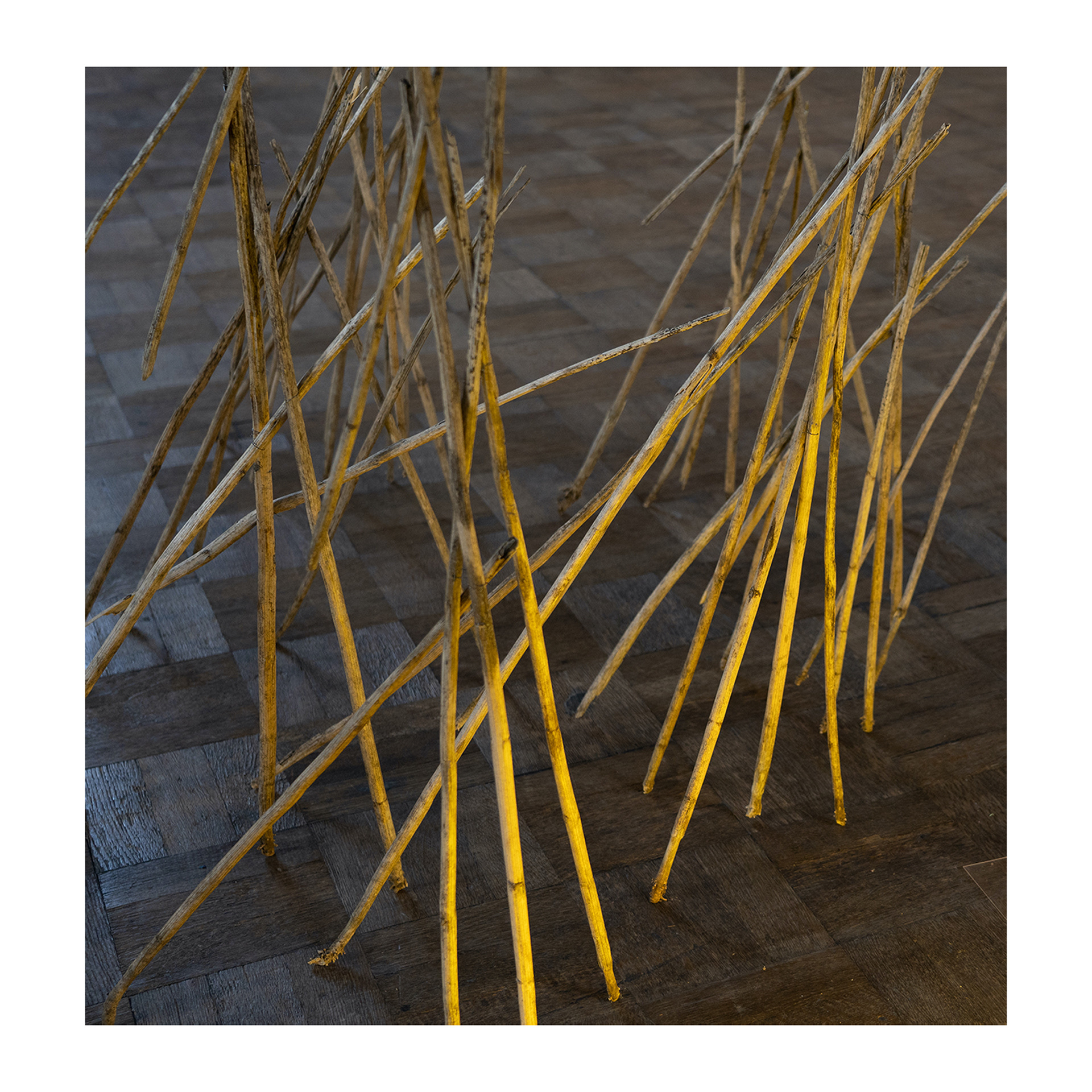

This work is a fragile and precarious ‘on-the-point-of-collapse’ event which relies on the interconnectedness and cooperation of all its elements to exist and function. This includes viewers’ amended behaviour. Viewers are obliged to slow down and become more spatially and socially aware of their surroundings, themselves, and others.

Sound of the Outmarsh reminds us that we must be prepared to alter course and that our future relies on a political, social and emotional transformation that sees humans inextricably interconnected with the natural world.

The ephemeral material used in this work was gathered from ancient fields in the marshy Witham valley in the heart of Lincolnshire's outmarsh. The stalks were assembled and organised to generate the sense of a unified force moving forward through the vast nave of the former church of St John the Divine in Gainsborough: their inferred migration orchestrated to reflect the dynamic properties and potential of marshland ecologies to change course and adapt to its changing circumstance.

By persistently and systematically flying DJI drones lower and lower over this installation, its manufactured collapse is inevitable. This was always going to be - just a matter of time.

As sites for more-than-human dramas, landscapes are radical tools for de-centring human hubris. Landscapes are not backdrops for historical actions; they are themselves active.

Watching landscapes in formation shows humans joining other living beings in shaping worlds."

Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World, (Princeton), 2015.